Lake Urmia’s Saline Desiccation Crisis: Understanding the Hydrology Behind Iran’s Vanishing Salt Lake

- Zahra Goudarrzipour

- Dec 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 20, 2025

Zahra Goudarzipour,

IESO 2025 Islamic Republic of Iran national team member, Young Scholars Club, Tehran, Iran

Introduction

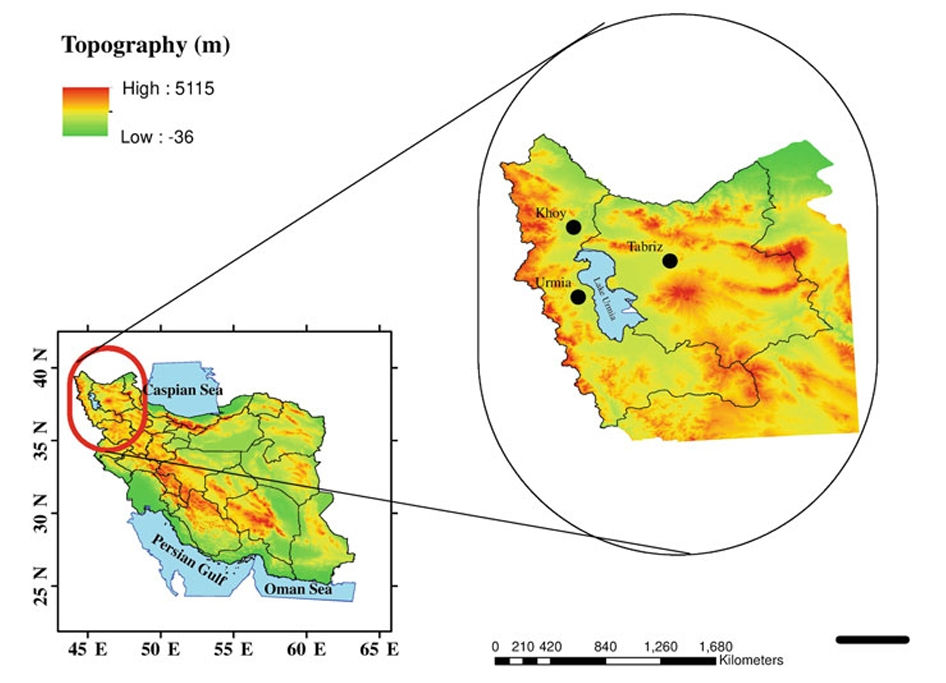

Lake Urmia is a shallow semi-transboundary hypersaline waterbody in northwest Iran (Fig. 1). It is known as one of the largest continental salt lakes in the world. The lake was declared a Wetland of International Importance by the Ramsar Convention in 1971 and designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1976.

Lake Urmia is a closed basin, and there is no outflow to external water bodies. In recent decades, due to the combined influence of climatic and anthropogenic factors, the surface area and volume of the lake have been shrinking significantly. If this lake follows the same fate as the Aral Sea and in the case of the complete dry-out of Lake Urmia, a vast salt desert will form, which is an undeniable threat to the local ecosystem and will trigger a chain of drastic alterations in the regional environment, resulting in ecological, agricultural, and social challenges. (Peygham Ghaffari, 2023).

There have been some attempts at rehabilitation and restoration of Lake Urmia. To address the unsustainable situation, the government of Iran announced a national ten-year program, the “Urmia Lake Restoration Program” (ULRP), in July 2013 (Shadkam et al., 2020).

Causes of Lake Shrinkage

The primary causes of water loss in Lake Urmia are evaporation and limited freshwater inflow. The lake has been affected by climate change, such as temperature increase and rainfall decrease, and also, excessive agricultural water use. These combined factors have accelerated the lake’s shrinkage and salinity rise. (Ghaffari & Yakushev, 2023)

The increase in water usage in the watershed of Lake Urmia and the decrease in

water inflow to the Lake due to the construction of nearly 50 large dams (Mahdi Taraghi, 2025) and the Urmia Causeway (Nasim Hossein Hamzeh, 2023) have accelerated the decay of the Lake elevation and increase of salinity and salt precipitation in the Lake in recent years (Fig. 2). (Siadatmousavi & Seyedalipour, 2023)

A global study showed that lakes are warming by about 0.34 °C per decade—faster than the oceans or atmosphere—intensifying evaporation from Lake Urmia (O’Reilly et al., 2015).

The Decline of Lake Urmia

Two central problems have recently been recognized and defined in terms of water quantity and water quality:

Water quantity: From 1995 to 2014, the water level has declined drastically (Fig. 3).

Water quality: The lake depression and salinity increase have affected the water quality (Ghaffari & Yakushev, 2023).

As river inflows declined and water demand rose, salinity exceeded 500 g/L in 2017, making the lake one of the most saline in the world. (Fig. 4-5) Such a high value of salinity significantly suppresses the evaporation from the Lake. The annual evaporation ranged from 730 to 970 mm in 2017 based on in situ measurements.

The sharp reduction in both surface area and volume since 1995 is illustrated in Fugure 3.

More than 102 islands exist in Lake Urmia that, during lake level low-stands, many of them are connected to the mainland; however, in high-stands they are largely inundated, and elevated parts remain above water level.

Effects of Lake Urmia Drought

The declining water level and rising salinity have led to salt-crystal formation and the loss of key species such as Dunaliella salina and Artemia salina. (Fig. 6). Desiccation and shrinking the Lake also increase the chance of salt dust, which results in progressive soil salinization and growing continentality of local climate. (D. Arab, 2016) Public health, access to drinkable water, migrations due to changing landscapes, and consequences of vanishing wildlife are all matters that turn out to rely on stable climatic and hydrologic conditions. The socio-economic consequence for the people who are living in that region was huge, and it has already triggered some migration waves (Peygham Ghaffari, 2023).

Restoration Project: Progress and Challenges

The worsening condition of Lake Urmia, combined with the government’s commitment to address this environmental crisis, led to the establishment of the Urmia Lake Restoration Program (ULRP). (D. Arab, 2016) An increase in water level and a relative improvement in Lake Urmia’s condition have been observed since 2017 (Zahir Nikraftar, 2021).

The main actions that have had a profound impact on increasing the volume of water entering the lake are listed here: All developed or under-developed dam projects, irrigation and drainage network construction were stopped, which could conserve 1,275 million cubic meters of lake's water right; 576 million cubic meters water from dams were released during two last years; Rivers poured into the lake were dredged; 131 million cubic meters wastewater were transferred from the existed treatment plants ; Controlling and decreasing water withdrawal from surface and groundwater resources have produced 90.3 million cubic meters water saving; Improvement water productivity in irrigation network and agricultural section led to 78 million cubic meters water saving.

Although these helpful actions have already been taken, the present condition of Urmia Lake does not match the anticipations in the road map. Despite these actions, the lake level remains 28 cm below projections, highlighting implementation challenges. (D. Arab, 2016)

Solutions for The Future

Since water transfer projects are time-consuming while the current status of the lake is crucial, short-term actions should focus on reducing agricultural water use, applying modern irrigation systems, and releasing reservoir water. Finally, by applying different restoration strategies such as reducing water consumption, transferring water from Silveh and Zab basin and unconventional water resources within the basin, the revitalization process will require at least a 10-year period. (D. Arab, 2016)

Even with improved management and artificial water conveyance, full restoration of Lake Urmia may no longer be achievable due to irreversible geomorphological changes (Peygham Ghaffari, 2023).

Conclusion

Our Role in Saving Lake Urmia

This report summarized the causes, impacts, and restoration efforts of Lake Urmia. Further international cooperation and public awareness are essential. Raising awareness, supporting restoration programs, and promoting sustainable water management are key to preserving Lake Urmia for future generations.

References

AghaKouchak, A. N., Hamidreza & Madani, Kaveh & Mirchi, Ali & Azarderakhsh, Marzi & Nazemi, Ali & Nasrollahi, Nasrin & Farahmand, Alireza & Mehran, Ali & Hassanzadeh, Elmira. (2014). Aral Sea syndrome desiccates Lake Urmia: Call for action. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2014.12.007

D. Arab, M. T. (2016, March 28-30). Urmia Lake Restoration Program U.S.-Iran Symposium on Wetlands, Irvine, California.

Ghafarian, P., Tajbakhsh, S., & Delju, A. H. (2023). Analysis of the Long-Term Trend of Temperature, Precipitation, and Dominant Atmospheric Phenomena in Lake Urmia. In P. Ghaffari & E. V. Yakushev (Eds.), Lake Urmia: A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate (pp. 149-167). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2021_740

Ghaffari, P., & Yakushev, E. V. (2023). Introduction: Lake Urmia – A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate. In P. Ghaffari & E. V. Yakushev (Eds.), Lake Urmia: A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate (pp. 1-8). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2023_1005

Lahijani, H. A. K., Hamzeh, M. A., Yakushev, E. V., & Rostamabadi, A. (2023). Salt Load Impact on Lake Urmia Basin Volume. In P. Ghaffari & E. V. Yakushev (Eds.), Lake Urmia: A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate (pp. 267-274). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2021_808

Mahdi Taraghi, L. Y., Eduardo S. Brondizio, Ali K. Ghorbanpour, Hojjat Mianabadi, Behzad Hessari. (2025). From abundance to aridity: The institutional drivers behind Lake Urmia's decline. Environmental Development, 55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2025.101205. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211464525000715)

Nasim Hossein Hamzeh, K. S., Kaveh Mohammadpour, Dimitris G. Kaskaoutis, Abbas Ranjbar Saadatabadi, Himan Shahabi. (2023). A comprehensive investigation of the causes of drying and increasing saline dust in the Urmia Lake, northwest Iran, via ground and satellite observations, synoptic analysis and machine learning models. Ecological Informatics, 78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102355. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1574954123003849)

O'Reilly, C. M., Sharma, S., Gray, D. K., Hampton, S. E., Read, J. S., Rowley, R. J., Schneider, P., Lenters, J. D., McIntyre, P. B., Kraemer, B. M., Weyhenmeyer, G. A., Straile, D., Dong, B., Adrian, R., Allan, M. G., Anneville, O., Arvola, L., Austin, J., Bailey, J. L.,…Zhang, G. (2015). Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophysical Research Letters, 42(24), 10,773-710,781. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066235

Peygham Ghaffari, E. V. Y. (2023). Lake Urmia: A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate (Vol. 123). Springer.

Shadkam, S., van Oel, P., Kabat, P., Roozbahani, A., & Ludwig, F. (2020). The Water-Saving Strategies Assessment (WSSA) Framework: An Application for the Urmia Lake Restoration Program. Water, 12(10), 2789. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/12/10/2789

Sharifi, A., Esfahaninejad, M., & Kabiri, K. (2023). Hydroclimate of the Lake Urmia Catchment Area: A Brief Overview. In P. Ghaffari & E. V. Yakushev (Eds.), Lake Urmia: A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate (pp. 169-185). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2021_809

Siadatmousavi, S. M., & Seyedalipour, S. A. (2023). Seasonal Variation of Evaporation from Hypersaline Basin of Lake Urmia. In P. Ghaffari & E. V. Yakushev (Eds.), Lake Urmia: A Hypersaline Waterbody in a Drying Climate (pp. 9-25). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2019_395

Zahir Nikraftar, E. P., Seiyed Mossa Hosseini, Behzad Ataie-Ashtiani. (2021). Lake Urmia restoration success story: A natural trend or a planned remedy? Journal of Great Lakes Research, 47(4), 955-969. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2021.03.012 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0380133021000721)

Comments